Echoes from History: Designing Self-Sovereign Identity with Care

This article was originally published as an advance reading for RWOT12 in Köln, Germany on August 9, 2023. It has been slightly edited for this reprint.

ABSTRACT: Self-sovereign identity represents an innovative new architecture for identity management. But, we must ensure that it avoids the pitfalls of previous identity systems. During World War II, two identity pioneers, the Dutch Jacobus L. Lentz and the French René Carmille, took different approaches toward the collection and recording of personally identifiable data. As a result, 75% of Dutch Jews fell victim to the Holocaust versus 23% of the Jews in France. Our foundational work on self-sovereign identity today could have similar repercussions down the road, so it’s imperative that we design this foundation responsibly with diligence and foresight, especially as the threat of significant regime change toward authoritarian governments looms ever larger across the world.

On January 26, 2020, on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz during World War II, Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the Netherlands offered a historic apology for how the country had failed its Jewish citizens during that War, which resulted in over 100,000 of them being deported and murdered by the Nazis. He acknowledged that one of the problems was the Netherlands’ civil service, stating: “When state authority became a threat, our public institutions failed in their duty as guardians of justice and security. To be sure, within the government too there was resistance on an individual level. But too many Dutch officials simply did as they were told by the occupying forces.”1

A similar acknowledgement had been offered almost 25 years earlier by President Jacques Chirac of France, who stated that “the criminal folly of the occupiers was seconded by the French, by the French state”.2 In France, some 76,000 French and foreign Jews were deported by the Nazis, but it was from a larger population that also had a larger demographic of Jewish peoples.

When distilled down to the bare and heartless statistics, the difference between the countries is stark: in the Netherlands, 75% of Jews tragically lost their lives, compared to 23% in France. The difference lies in how each country dealt with identity: what they were willing to record and what they were not. Since regimes inevitably change, since data inevitably changes hands from one person to another, this type of consideration is crucial.

It is especially crucial today because regimes have been changing quickly and drastically across the world and many of the new governments have been raised up through their declarations of intolerance and hatred. The freshest example is ironically in the Netherlands, where Islamophobe and isolationist Geert Wilders’ PVV party won a plurality of votes, giving him the opportunity to become Prime Minister3. He’s promised to ban the Quran, and one shudders to think of what he might do with identity records of Muslims. But, he’s far from alone. Victor Orbán, the authoritarian Prime Minister Hungary, has conducted attacks against the LGBT community4. Marine Le Pen has made increasingly credible runs for French President as the head of the National Front. In the United States, Donald Trump, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, and even the Supreme Court have attacked disadvantaged peoples and taken away rights. Many of these ingredients are the same as those seen in World War II, but our data collection has reached new heights, and thus offers even greater dangers.

These harsh lessons remain especially important for the new technologies of digital identity, which have boosted information compilation even beyond that of the physical world. That includes both self-sovereign identity, an ideology to reclaim human dignity and authority in the digital world and an emerging suite of applications designed to enable that movement, and other new digital-identity systems. We must heed the grave lessons of history as we look forward, to ensure that digital identity technology of all types is never used in a similar genocide.

Impeccable Identity: Lentz’s Tragic Legacy

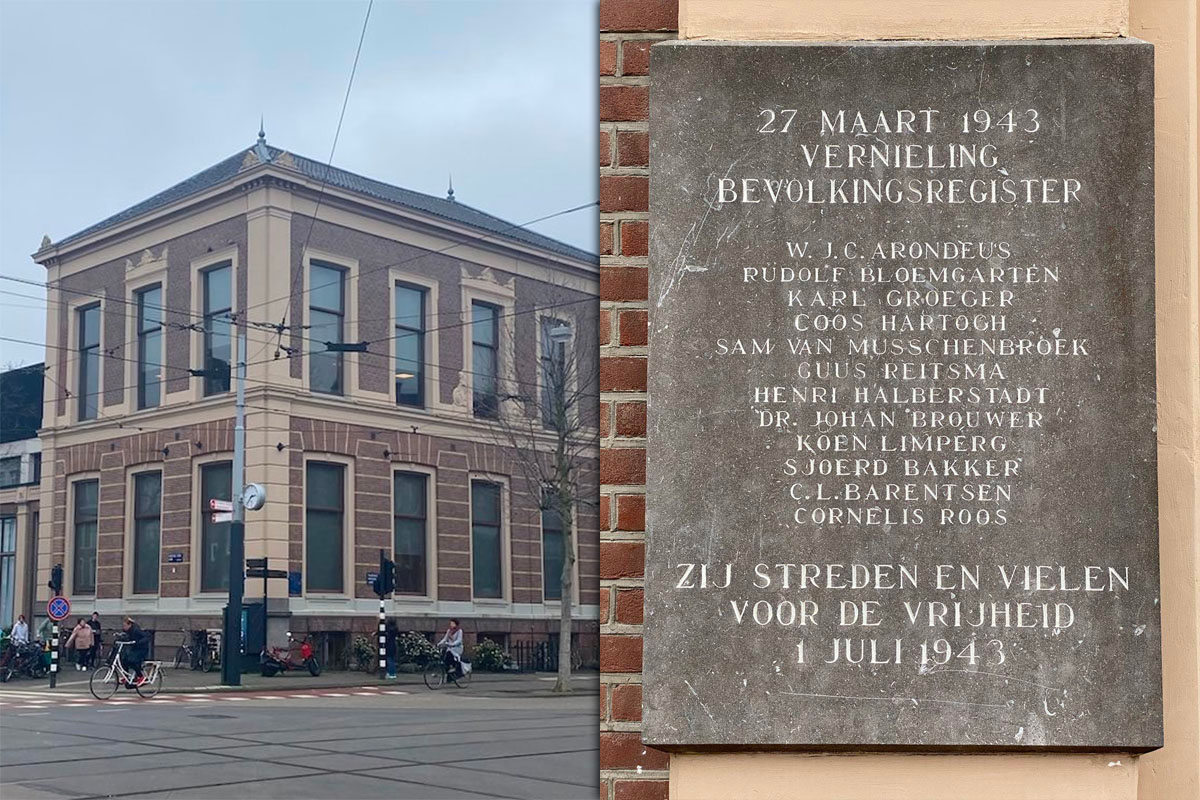

The story of identity in the Netherlands during World War II is still writ on the landscape of Amsterdam today, at the National Holocaust Names Monument, where Prime Minister Rutte gave his famous speech in 2020, and a few blocks away at the intersection of Plantage Kerklaan and Plantage Middenlaan, where the municipal building that held the records of the region’s population once lay.

Today, there’s nothing special about the structure that once housed the records building, other than a somber plaque affixed to a wall. It reads, “27 Maart 1943: Vernieling Bevolkingsregister”. March 27, 1943: Destruction of the population register. Therein lies the crux of the story of how the Netherlands recorded too much identity information, and how they made one last attempt to destroy it after the Nazis gained control of the country.

That story begins, as Prime Minister Rutte acknowledged, in the Dutch Civil Service, which the Nazis recognized as “Germanic” in its orderly thoroughness. So much so that they left the cadres of Dutch civil servants alone to run things, with Germanic leadership installed above them. In particular, the story begins with one operational functionary by the name of Jacobus L. Lentz.

In 1932, Lentz was appointed the head of the National Inspectorate of Population Registers in The Netherlands. This was a critical post in the 1930s because of the Great Depression: the Inspectorate ensured that all citizens had equitable access to basic services. Thanks to its efficiency, the small nation fared better than even the greatest European powers during the 1930s, helping to keep its citizens out of the poverty that was blanketing the globe. Looking to ensure that this happy efficiency was maintained and even bettered, the Dutch government tasked Lentz with promoting yet greater order by bringing consistency and uniformity to population registers throughout the country.

Lentz was thus instrumental in what followed. By 1936, a decree required that every resident in the Netherlands must have a personal identity card, one copy to be carried on their person and a duplicate to be filed in the civil archives. These archives also contained a cornucopia of personally identifying information, including gender, race, ethnicity, occupation, residence, familial relations, and religion. They were centralized in a single office in each officially recognized region of the Netherlands, all of which used the same systems so that the data was interoperable, ensuring that Lentz’s data was useful in civil governance and planning.

Lentz meticulously rationalized, standardized, and organized the Netherlands records held in that building at the intersection of Plantage Kerklaan and Plantage Middenlaan. Thanks to him, the comprehensive efficiency of the archives, which even incorporated special filing cabinets of his own patented design aimed at expediting searches and cross-checks, made it possible for the Netherlands to provide amply and justly for its citizens during the depths of the greatest economic crisis in modern world history. This aligned with Lentz’s vision of creating “the paper man.”5 His work was recognized at the highest level by a royal award bestowed on him by no less a figure than nation’s queen.

The thoroughness and accessibility of the centralized registries throughout the Netherlands made them high-priority targets for capture by the Nazi invaders following their occupation of the Netherlands in May 1940. The Nazis understood their immense value in accelerating the hunt for Jews and other “undesirables”. Lentz himself was recognized as an especially valuable local asset. No sooner did the Dutch government capitulate than occupation authorities asked him to create a comprehensive national personal identity card that was extremely difficult to alter or forge. For Lentz, this, in fact, had been a pet project for years, one his superiors had consistently resisted as being “un-Dutch.” Now he was being asked to do it! He tackled the project with remarkable enthusiasm.

Soon, Lentz had cards that could be compared against the corresponding files in a central civil registry, which he had redesigned for accessory and access. Even if a card was forged, the registry was thus a backup. By September 1941, these cards and files included a thorough census of Dutch Jews, each of whom now carried a card emblazoned with a large letter J.

On the night of March 27-28, 1943, resistance operatives, some of whose names are incribed on that plaque, disguised themselves as local police officers, and, in a daring operation attempted to burn down the registry and the files it housed. Brilliantly planned and executed though it was, the attack fell short of achieving its objective. To be sure, some 800,000 identity cards fell victim to the flames and flood, but, that destruction only amounted to 15 percent of the registry’s records. It was soon back in business, and the Jewish genocide ramped up.

Lentz was arrested by Netherlands police in May 1945 for his collaboration with the Nazis and eventually sentenced to three years in prison. But it was far too late. This perfection of record keeping, this creation of a “paper man” who could be cross-referenced through a closely held certificate and a central registry, was core to the high rate of murder of the Netherlands’ Jews, which Prime Minister Rutte apologized for on that cold winter day in 2020.

This dark chapter should serve as a stark warning for our work on self-sovereign identity — as should the fact that things can be very different, as evidenced by a similar situation in France with a very different conclusion.

Subversive Systems: Carmille’s Quiet Resistance

In France, the story instead begins with René Carmille, an engineer, a World War I officer, and a spy for France’s Deuxième Bureau during the first World War. His own move toward the registration of identity came not because of the Great Depression, but instead the needs of the military.

Carmille’s work was founded on early punch-card technology, something that had also been used in The Netherlands, but was more central to Carmille’s work in France. By 1935, he was developing a registry for the French army that was to be used for conscription and mobilization. Carmille proposed a twelve-digit personal registration number as the core of this registry (which later became 13 digits after the occupation and division of France). This ID could be used to determine a person’s date of birth and place of birth, as well as a “complete personal profile”6, which included details on professional skills and well as other attributes.

By 1940, the Nazis were attempting to produce censuses of the Jews in France, but they were facing notable obstacles. Prime among them was the fact that the government had not polled on the question of religion since 1872 and had no interest in doing so now. There also weren’t sufficient electronic tabulators to catalogue the results from France’s immense population: France instead depended on Remington typewriters or even pen and paper for much of their tabulation.

Enter René Carmille. In November 1940, he created France’s “Demographic Service in Vichy”, opened offices on both sides of the occupation border running down the middle of France, contracted for 36 million Francs worth of tabulating machines, and announced plans for a new census of French citizens. He would replace the “anarchic” methodology that France had previously used to record census data with something more modern; afterward, French citizens would have to carry “uniform identity cards”, which linked to precise details on vocational expertise. Carmille’s new census would also reverse France’s long-standing omission of religious data by including data in “column 11” that would require participating Jews to not only report their own religion, but also that of their grandparents. Like Lentz, Carmille ultimately had his own version of a paper man, saying: “We are no longer dealing with general censuses, but we are really following individuals.”7

It appeared to be exactly what the Nazis were seeking.

If Carmille had ever properly tabulated this data, the results likely would have been similar to those in the Netherlands: identity turned to discrimination and ultimately genocide. But, that didn’t happen. Instead, Carmille purposefully programmed his machines to never punch data for column 11 and hid more than 100,000 punched cards of Jews in his office. Call it an early form of data minimization and selective disclosure8. Carmille ensured that the personal data most likely to harm people was not made available to the people most likely to use it for harm.

There is some disagreement about Carmille’s role in the Vichy government and what damage he might have done there. However, the historical data seems to support him continuing to be a counter-intelligence officer, and that he purposefully sabotaged the census of the Jews while simultaneously using his data collection appartus to compile a listing of 800,000 French soldiers ready to rise up against the German occupation, 300,000 of them who were ready for near instaneous mobilization. Which was exactly what happened: on December 5, 1942, French troops captured the French National Statistics Service office in Algiers and used Carmille’s data to mobilize thousands of French troops.

René Carmille was arrested by the Nazis in February 1944, interrogated by a Nazi torturer, and sent to Dachau, where he died in January 1945. Though his work may have saved the lives of tens or even hundreds of thousands of Jews in France, it required sacrifice.

Once we collect identity data, its use is almost inevitable: pushing against that tide is the work of giants.

Two Models, One Truth

Self-sovereign identity has a dual nature.

On one hand, there exists a clear need for more defined identity. This was the main focus for self-sovereign identity when it was first discussed at RWOT2 and ID2020 in 2016. Then, one of our primary use cases was the stateless refugee who could be denied access to government services. It echoed (albeit with better foresight) the challenge that Jacobus Lentz faced with migration in the 1930s, when he put together a system to make sure all Dutch could have access to civic support during the Great Depression.

Conversely, there’s a call for minimizing identity data. This asks a crucial question that’s of both historical and ethical importance: What is the minimum identifying data access necessary to give you the right to be able to do things without unduly impinging on your privacy, dignity, and entitlement to respect? It builds on the truth the René Carmille discovered as he purposefully excluded religious information from his census: personal information can be dangerous, damaging, and even deadly.

Often, we share our personal details and other identity, erring on the side of oversharing, grounded in our current trust toward the data collector. The contrasting approaches of Lentz and Carmille demonstrate why that isn’t sufficient: the regime can always change. The intended use of data can be easily misinterpreted or manipulated. Lentz’s Great Depression data could be used by the Nazis to genocide Dutch Jews; and what the Nazis thought was their French Census Data could be used by Carmille to raise an army. And this isn’ just a historic concern: under Trump’s administration, there were similar attempts to repurpose the voluntary registrations of “Dreamers” from the previous administration, threatening residents who illegally entered the country as children with deportation.

Ultimately, data will be used to the fullest extent that it can be and it may be used for the worst purposes possible, entirely at odds with the original purpose of the collection. As architects of the next generation of self-sovereign identity systems, we must prioritize user empowerment, enabling each individual to fully control their identity. We have to think about strategies of data minimization and selective disclosure. We have to consider what data needs to be collected, and what does not. We do not want to make a new paper (electronic) man.

We must instead remember the past when identity was weaponized and six million and more died as a result. But we need to operationalize that remembrance by transforming it from reflection into a vision for the present and the future. Call it remembering forward. Call it foremembrance.

Conclusion

The time for action is now. The dreams of self-sovereign identity that were first imagined at RWOT2 and ID2020 have been made realities by standards such as DIDs9 and Verifiable Credentials10. Numerous companies have emerged to support these standards, while governments are beginning to adopt them. Simultaneously, the European Union is in the process of rolling out eIDAS11 as an ecosystem of electronic identity. We are at a tipping point where the standards for future identity will be set in the days, months, and scant years ahead.

At this crossroads, we could go the way of recording too much information. We could create great honeypots of data for use or abuse by future regimes, or even by criminals. By recording our gender, our sexual orientation, our religion, our political affiliation, or even just our favorite books, movies, and songs, we could open ourselves up to future discrimination or worse. This would be the way of Lentz.

But there’s another path, one that normalizes the minimization of information. As self-sovereign identity designers, we must ask if we are protecting our users; we can do so by following the original goals of self-sovereign identity, by allowing the person represented by an identity to decide what information goes out. Simultaneously, we can do our best to influence the design of eIDAS and other more centralized systems to similarly adopt rules of data minimization and selective disclosure. This would be the way of Carmille.

We are a crucial crossroads in the design of digital identity. When the next history books are written, we must be Carmille, not Lentz.

The Path to Self-Sovereign Identity Links

Christopher Allen is a long-term advocate for self-sovereign identity. He popularized the term and laid out an initial set of principles in his foundational article, “The Path to Self-Sovereign Identity”, coauthored the DID spec for W3c, and founded the Rebooting the Web of Trust workshops that advanced the technology for a decade. Following are articles by him and interviews with him on the topic.

- The Co-Writer of TLS Says We’ve Lost the Privacy Plot (4/24/25): An interview with Tereza Bízková for Hackernoon on how things have gone wrong.

- SSI Orbit Podcast: Christopher Allen Interview (1/31/25): Following up the “Has Our SSI Ecosystem Become Morally Bankrupt?” article, a discussion of the problems with the current SSI ecosystem.

- Echoes from History (11/15/23): How identity went horribly wrong during WWII and the warnings that offers for the future of self-sovereign identity.

- The Origins of Self-Sovereign Identity (8/9/23): Living Systems Theory, Ostrom’s Principles, and other foudndational ideas that led to SSI, and what they say about its intent.

- Private Key Disclosure (8/16/22): Digital identities are secured by private keys, but are private keys secure from the government?

- Principal Authority: A New Perspective on Self-Sovereign Identity (9/15/21): A new lens for looking at Self-Sovereign Identity, based on successes in the Wyoming legislature.

- Self-Sovereign Identity: Five Years On (4/26/21): Five years after “The Path to Self Sovereign Identity”, the successes and challenges of SSI to date.

- The Path to Self-Sovereign Identity (4/26/16): The initial article on SSI, including the ten principles for Self-Sovereign Identity.

Footnotes

-

Uncredited. 2020. “Prime Minister of the Netherlands Issues Historic Apology”. International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/news-archive/prime-minister-netherlands-issues-historic-apology. ↩

-

Simons, Marlise. 1995. “Chirac Affirms France’s Guilt in Fate of Jews”. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1995/07/17/world/chirac-affirms-france-s-guilt-in-fate-of-jews.html. ↩

-

Faiola, Anthony, EMily Rauhala, and Loveday Morris. 2023. “Dutch Election Shows Far Right Rising and Reshaping Europe”. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/11/25/europe-far-right-netherlands-election/. ↩

-

Beauchamp, Zack. 2021. “How hatred of gay people became a key plank in Hungary’s authoritarian turn”. Vox. https://www.vox.com/22547228/hungary-orban-lgbt-law-pedophilia-authoritarian. ↩

-

Rood, Juriën. 2022. Lentz, msp. 45. English translation of the original Dutch manuscript of a book in progress. ↩

-

Black, Edwin. 2001. IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation, p. 321. ↩

-

Black, Edwin. 2001. IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation, p. 323-324. ↩

-

Allen, Christopher. 2023. Musings of a Trust Architect: Data Minimization & Selective Disclosure. https://www.blockchaincommons.com/musings/musings-data-minimization/ ↩

-

W3C. 2022. DIDs v1.0. https://www.w3.org/TR/did-core/. ↩

-

W3C. 2022. Verifiable Credentials Data Model. https://www.w3.org/TR/vc-data-model/. ↩

-

European Commission. Retrieved 2023. eIDAS Regulation. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/eidas-regulation. ↩