Protecting Your Wellness Data with Hashed Elision

Or: How to Stay Heart Healthy, but Not Become the New Fitbit Murderer

Many of us have heard of the Fitbit murder case: a husband killed his wife and then lied about there being a third party involved, but her Fitbit data contradicted his fabrications and ultimately exposed him as the murderer. There’s a lesser-known case from the same time when someone was charged with arson and insurance fraud based on data from his pacemaker.

We have worked with privacy absolutionists, and understand the important arguments for that stance, but likely most people won’t get too worked up by a murderer and an arsonist being hoisted by their wellness-info petards. Nonetheless, these cases point toward the enormous amounts of data that tend to be stored in wellness apps and hardware such as Fitbits and pacemakers. That information could be used for even worse purposes.

Just imagine some of the following scenarios:

- Insurance Discrimination. A Fitbit records heart information that reveals an arrhythmia. If politicians in the United States succeed in overturning the rest of the ACA, something that would have happened in 2017 if not for a single vote from Senator John McCain, insurance companies could once more discriminate in the individual insurance marketplace, and this sort of data would be a prime vector for doing so: your Fitbit data could be required before you were issued insurance. Even without an arrhythmia, you might be charged higher rates if you didn’t exercise enough!

- Misogynistic Prosecution. Several states in the US have not just outlawed abortion but are working to make it illegal for their residents to seek reproductive care in other states. Because body temperature information can be used to mark a woman’s ovulation, it could be subpoened by these states to maliciously prosecute women by suggesting that they had previously been pregnant.

- Location Spying. Early activity trackers recorded GPS information through phones, but newer trackers have built-in GPS. Though not technically health-related, this can be very dangerous information that could be used to reveal where a person went and who they met. Obviously, this might be used to weed out corporate espionage or to reveal adultery (or possibly to falsely accuse someone of either). But imagine a conservative company who fires someone for visiting a strip club or a progressive company who fires someone for attending a Trump rally. If you want to go beyond theory and imagination, how about the priest who lost his job because his geolocation data was leaked. That was apparently based on an app, not a tracker, but the principle remains the same.

Despite all the potential dangers (and there are many more), wellness data like that stored in a Fitbit or an Apple watch is also something we want to share. We want to be able to provide our doctors with extensive data; we want to stream data for our kids or elderly parents, so that we can be alerted if a problem arises; and we want to contribute to public health by participating in clinical studies and by supporting contact tracing for viral diseases. Activity trackers and other health monitors can dramatically reduce the overhead of collecting and sharing this data, and that can make us all healthier.

If we can just make it safe.

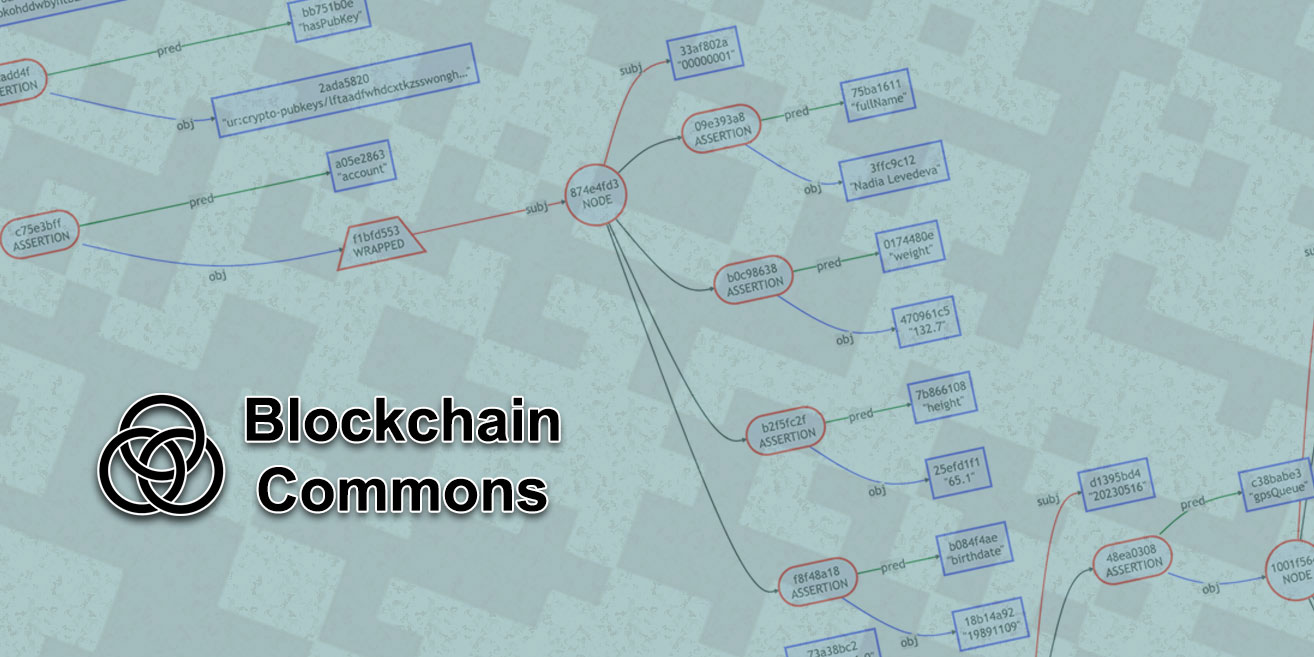

That’s where holder-based hashed elision like that in Gordian Envelope comes into play. Data can be removed, so that only hashes of the data remain, hashes that are built up into a Merkle Tree that checksums the entire data set. Because it’s holder-based, any user can selectively elide their own information, ensuring minimal disclosure to another party — and disclosure that’s entirely the decision of the holder. Because it’s hashed, signatures for the data will remain valid, allowing for continued authentication and ultimately guaranteeing the provenance of data.

With this functionality, information can be strongly protected, so that other parties just don’t have the ability to access your data; while you can still choose to give it out in limited quantities. Meanwhile the signatures and the hashes ensure the auditibility of the data, which is critical for public health use cases such as clinical studies. Holder-based, hashed elision is an excellent and simple solution to address many of the dangers of wellness data.

Research institutes are investigating other possibilities for protecting wellness data, such as homomorphic encryption. CL Signatures and BBS+ Signature schemes offer still more possibilities to create anonymity and to foil correlation. The problem is that many of these methodologies are complex and costly. As a result, they can’t be done on constrained devices such as activity trackers. Conversely, hash-based elision is very simple: Gordian Envelope builds its hashed Merkle Tree with SHA-256, specifically because it works well with constrained devices. (The particular design of Gordian Envelope also offers some additional advantages, such as the ability to elide not just data, but structure as well.)

We have recently published a set of use cases that detail: how wellness data can be protected using Gordian Envelope; how it can be shared with medical profesionals and other parties and how salting can reduce correlation; how it can help clinical trials; and how it could support contact tracing, such as with COVID. These use cases were developed in consultation with people doing wellness work, so we hope they’re thoughtful and realistic depictions of the needs of the wellness community and how they can be safely met using holder-based hashed elision such as Gordian Envelope.

As with our recent article on “The Dangers of Digital Credentials in Education”, we think that it’s most important to embrace privacy now with some sort of holder-based hashed elision, but we think Gordian Envelope offers a particularly strong way to do so.