The Dangers of Digital Credentials in Education

And How to Resolve them Using Holder-Based Hashed Elision

Digital credentials are the next step in credentialing because they’re quite simply a better way to share qualifications such as those generated at an educational institute.

- They simplify administration, because an issuer of credentialing qualifications (such as a college or university) just has to produce the credentials, sign them, and place their public key in a PKI and they’re done. There’s no need to constantly respond to credential-verification requests.

- They simplify usage, because a holder of credentials (such as a student) is able to offer them up without needing to check back in with their college or university: they have a fully verified copy of their qualifications that’s already signed.

- They increase reliability, because they make credentials much harder to forge (which is already a real problem and will become moreso in the world of AI). But, reliability isn’t just about the authenticity of the credentials: a student can also prove they’re the subject of a credential by producing a signature that matches a public key encoded into the credential. Finally, digital credentials also enjoy continued availability even if a credentialing institute shuts down.

There’s no doubt that digital credentials, verified by digital signatures, will soon be replacing traditional diplomas, transcripts, and certificates in education.

Unfortunately, the current state of digital credentials provides no support for privacy. Unless serious steps are taken immediately to incorporate privacy into digital credentials, bad practices are going to be baked into the foundation of this new methodology for reporting qualifications, and a whole generation of students will be at risk as a result.

The Threats for Students

Students whose educational qualifications have been recorded in digital credentials face two major dangers from those credentials.

The first is identity theft. Credentials tend to be data-rich. Because of the need to positively identify a student, they tend to include name, age, gender, address, student ID, and sometimes even more dangerous content. At the least, this is the exact data that is required for many identity questions, but it could also be extensive enough to fully steal an identity.

The second is discrimination. Much of the information within a credential could be used to discriminate against a student.

- A gender could lead to gender discrimination and can be especially problematic for transgender students.

- A name or address could lead to racial or ethnic discrimination, based on the ethnic origins of a name or the international location of an address.

- An age or credentialing date could lead to age discrimination.

- The name or location of the college or university could lead to racial or ethnic discrimination, political discrimination, or even religious discrimination.

- Specific courses taken could lead to racial discrimination, political discrimination, religious discrimination, or class discrimination, depending on what they were.

In short, a fully detailed credential can be a huge landmine for a student.

The Threat for Institutes

Digital credentials can also be threats to the issuing institutes.

Part of this is because governments are becoming increasingly protective of their citizens’ privacy. As a result, anyone who holds personally identifiable information (PII) can be subject to laws such as GDPR (in Europe) and CCPA (in California), which make them liable to stringent regulations for the storage, maintenance, and deletion of that PII. There are also laws specificly related to educational institutes, such as FERPA and the PPRA (in the United States).

More generally, PII is increasingly becoming a liability in the digital age. By holding extensive amounts of PII and by issuing credentials that contain the entire content of that PII, an educational institute can put itself in the hot seat.

Generally, the more PII that an digital educational credential holds, the more dangerous it becomes for both the student and the university. If there were a way to reduce the amount of data, it would innately make digital credentials safer, which is where holder-based hashed elision comes in.

Creating Privacy: Holder-Based Elision

The most obvious solution is to let a student elide data from their credential as they see fit. This supports data minimization, a general policy that maximizes privacy by minimizing the amount of data shared at any one time. More specifically, it allows a student to remove data from their digital credential that might be discriminatory and may even allow them to remove all of their PII, since they can prove ownership of the credential with a signature. As a result, credentials released out into the wild (to other institutes or to potential employers) are much less data-rich than would otherwise be the case.

For example, if a student were applying for an engineering job, and they’d received their degree from an Eastern European university, they might want to elide the name and location of the university (while maintaining information on its accreditation) and their own Eastern-European name (while proving their ownership of the credential with a signature), out of fear of discrimination toward Eastern Europeans in the technical field.

By allowing the holder of a credential to do this redaction, rather than depending on the college or university to constantly release new versions of the credential that are elided in different ways, considerable administrative burden is taken off of the issuing institute. It can also dramatically reduce their liability, because all questions of data retention and usage suddenly become issues for the student, not the university.

Ensuring Authenticity: Hashed Elision

The problem with eliding a signed document is that you will invalidate the signature. That’s where hashed-based elision comes in. It allows for elision while maintaining the authenticity of the credentials.

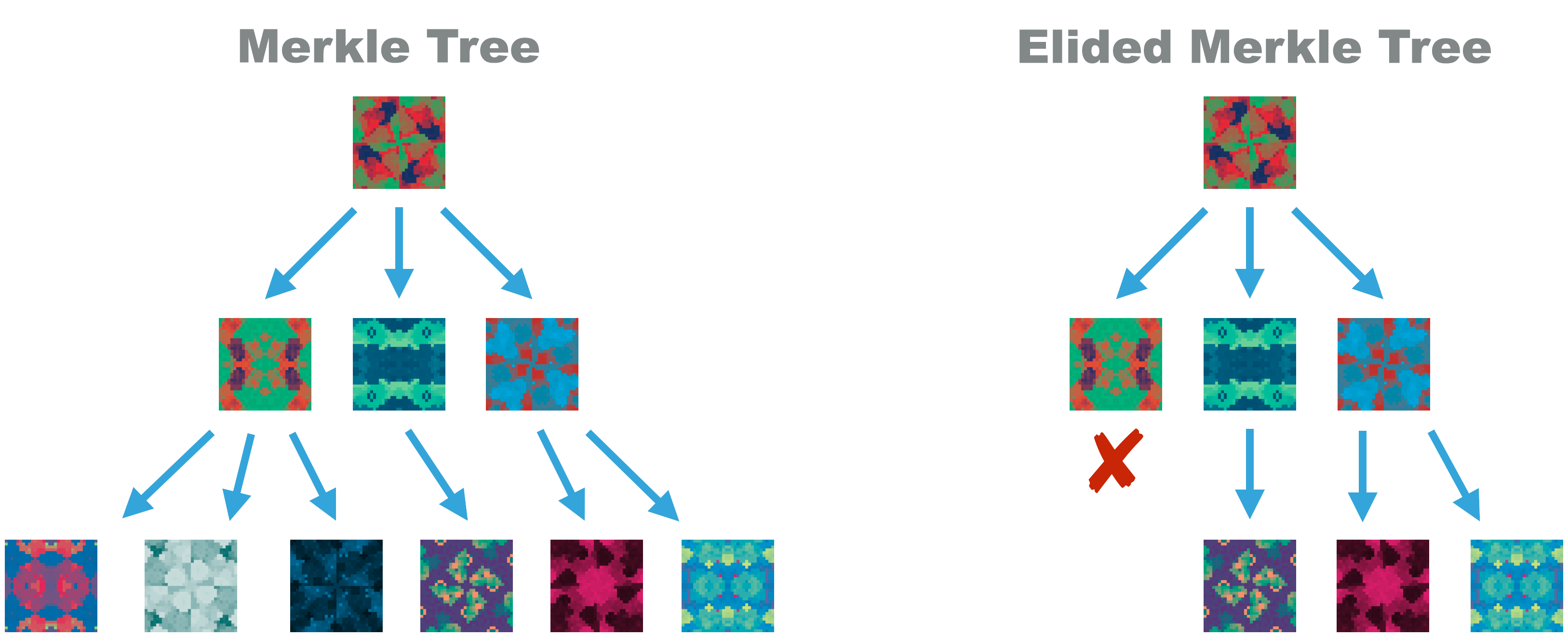

Hashed elision requires building a credential’s data into a Merkle Tree. This is a tree of data where each leaf is also represented by a hash, and where branches hash together the hashes from their leaves, until a single root hash is created to represent the entire tree.

Because hashing is a one-way function, there is no way to recreate the data from the hash. Because collisions are extremely unlikely in hashes, and can’t be purposefully created for any strong hash function, the hash is a relatively perfect representation of the unique data within the hash. As a result, a credential issuer can just sign the root hash and that’s as secure as signing the credential as a whole.

Doing so allows for elision: any leaf or branch of data can be entirely removed, leaving behind only its hash. The master hash remains valid because it’s based on the leaf and branch hashes; and the signature remain valid, because it’s applied to that master hash. This remains true even when some (or even all) of the data is no longer present.

The result? Full support of data minimization. The student is in control and makes all the decision about how their data is shared. The college or university has none of the responsibility and none of the liability.

Why Should Educational Institutes Care?

A number of the benefits for educational institutes have already been laid out.

Holder-based hashed elision …

- Removes administative burden.

- Reduces potential liability.

- Supports regulatory compliance.

Moreso, however, it goes to the core values of colleges and universities. It allows the institute to produce meaningful credentials while simultaneously protecting the students and their future. It not only supports and encourages diversity, but it also protects the entirety of a student body, as they tend to be a vulnerable category of people, who are just starting out their individual lives, away from home and their support structures for the first time ever.

Why Should Everyone Else Care?

The benefits of minimal disclosure, supported by holder-based hashed elision, don’t end with the students and their educational institutes. PII data can be quite toxic nowadays thanks to regulations such as GDPR and CCPA. Data elision can reduce it.

Though other entities will need credentials to verify qualifications, they won’t want anything more than they need. Holder-based hashed elision helps reduce the toxic data problem by minimizing everyone’s exposure to PII.

Hashed-Based Elision Can Do More

Though simple holder-based elision is the main use case for the hashed elision of educational certificates, once it’s in place it can also enable more powerful functionality such as progressive trust, proofs of inclusion, and herd privacy.

Progressive trust is a simple expansion of the holder-based elision philosophy. It suggests that a holder can slowly reveal more information over time, by producing less elided envelopes as more trust is gained for a counterparty. It’s the sort of thing that’s only possible when a holder doesn’t constantly have to go out to an issuer for new copies of their credentials.

Proofs of inclusion expand on the technology of hashes. They allow data holders to proactively prove that they are part of a master hash published by a credential issuer. Thus, for example, an educational institute could publish a master hash representing all of their scholarship students. They would not publish a specific list of those students, because this is private information that a student may or may not wish to reveal. Instead, they give each student sufficient data that they can prove they are part of the master hash, usually by providing them with the credential data that makes up their own leaf, and then a string of hashes that move from that leaf, up through branches, to the root.

This results in herd privacy. Because hashes are one-way functions, it’s impossible for anyone to ascertain that someone is part of a root hash (provided that the Merkle Tree has been created with sufficient privacy protections, such as the salting of individual entries). As a result, the student is again in total control: they get to decide whether to ever reveal that they’re part of the hash (or not).

Institutes may decide to never use functionality of this type: simple credentials based on holder-based hashed elision may be sufficient for them. But, if desired, they have expanded functionality to dynamically create progressive trust or to enable proofs of inclusion and herd privacy.

Final Notes

Digital credentials are powerful, but in their simplest form they don’t protect privacy. For educational credentials, this can leave both the student and the educational institute at risk.

Strong, safe, and private credentials require:

- Control by the holder.

- Elision by the holder.

- Maintenance of signatures through the hashing of data.

Embracing this technology now, before the first privacy disaster occurs in the educational credential world, is an imperative.

Blockchain Commons’ Gordian Envelope suggests a specific methodology for holder-based hashed elision. However, it’s the central idea that is crucial to ensure the privacy and protection of credential subjects, whether our specific technology is used or not.

For More

This topic was also presented to the Verifiable Credentials for Education Task Force at W3C. The slides and video of that presentation are included below:

Slides (PDF):

|

Video (YouTube): |